Our beer writer in residence Matthew Curtis is writing a three-part series on cask beer, from its history and its cultural impact, to the challenges it faces in today’s beer market. In part two he looks at various data associated with the sales and volume of cask being produced today, and asks if we’ve been looking at it all wrong. If you’ve not read part one yet, catch up with it here.

If you believe the numbers, sales of cask beer within the UK have been in freefall for the past few years. And yet, whenever I leave the house for a pint, I am constantly left in awe of the respect with which cask beer is treated, and the volume with which it’s consumed.

This is largely to do with where I live, in the North of England. In cities like Manchester, Leeds and Sheffield, and surrounding towns such as Huddersfield, Preston and Macclesfield, there’s a decent amount of drinkers like you and me who treat cask with a special reverence. But, for the most part, it is just treated as a normal, everyday, drinking beer. It is typically low in strength, which means you can have a few pints over the course of a session and not feel too done in. It also tends to be relatively affordable, with a nice, sessionable bitter still typically coming in at under £4, unless you’re in a particularly trendy bar that’s paying city centre rents. But still, it’s not too spendy.

These factors combined means that you can spend longer in the pub, which is really the point of this entire endeavour. Pubs as community spaces are essential for our well being. In today’s turbulent times, they provide the perfect place between work and home life, where you can put down your phone – for an hour or two at least – and escape from the world. Great beer, while never dominating these moments, is often central to our enjoyment of them.

Another notable fact about pubs in the North, and in particular, their customers, is an expectation of quality: clean lines, fresh beer, clean glassware. Pubs that don’t follow these three basic principles simply won’t sell as much beer as the ones that do. This, combined with a high throughput due to its popularity if these basic principles are adhered to, means that cask is typically the freshest beer on the bar.

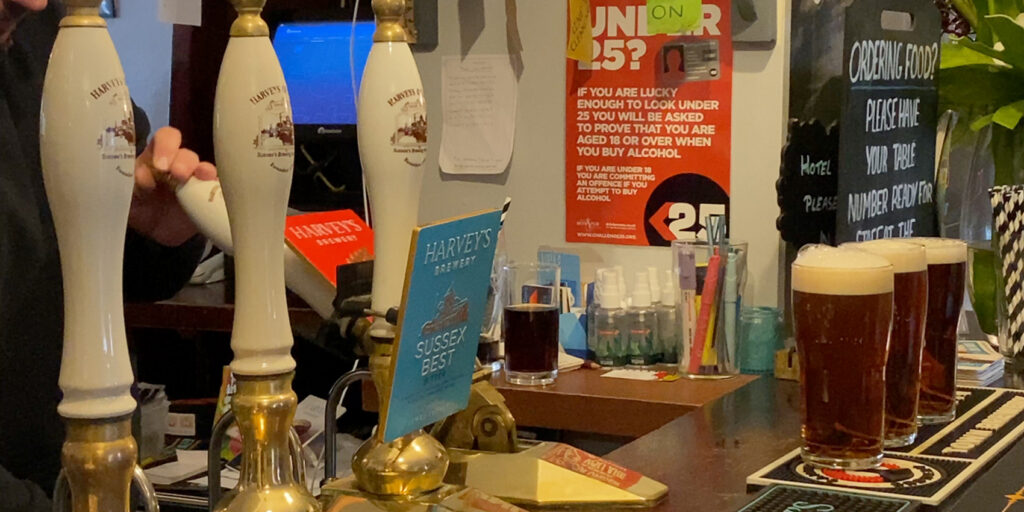

This fact is the central tenet of a new campaign that has been dubbed Drink Cask Fresh. The scheme is the brainchild of SIBA (The Society of Independent Brewers) and CAMRA (The Campaign for Real Ale), and aims to promote cask beer as ‘the freshest beer on the bar’ utilising brightly coloured point of sale materials it hopes will attract the attention of Generation Z (ages 18-25). It’s already garnered the support from a host of breweries, from traditional family brewers like Harvey’s and Timothy Taylors, to global giants including Asahi and Greene King. (The full list of supporters can be seen on the campaigns website here.)

At SIBAs annual Beer X conference, taking place in Liverpool this March, I attended a presentation about the campaign hosted by beer writer Pete Brown, who himself has been a vociferous supporter of cask ale for as long as he’s been writing about it. I learned about how the scheme is to be piloted in several pubs – mostly in the south and part of large pub companies – using everything from bright green bar runners, to day-glo orange neoprene sleeves that would wrap around hand pulls. The hope is that these sales aids will entice the gaze of younger drinkers who might usually choose a mass produced lager, or a cocktail (it’s worth noting that sales of spirits are presently booming among younger age groups).

In 2018 I reported for Good Beer Hunting on how cask beer had taken a 6.8% dip in sales according to the annual Cask Report, which is put together by Cask Marque – an independent industry body that monitors the quality of cask beer in the on trade. And while the following years report indicated that the market was stabilising, the two years after that saw pubs closed for a very long time, and you probably guess what that did to the sales figures for cask ale. The industry nosedived, and we are still crawling out of that Covid-19 induced hole.

More interestingly, there is plenty of data that suggest Generation Z is drinking less in general, with a staggering 26% of that age group choosing to not drink alcohol at all according to this report published in 2022 by the BBC. But what this data says to me is that three quarters of under 25s are still drinking, and that yes, we perhaps should be thinking about how to make sure that drink is a nice pint of cask.

The aim of Drink Cask Fresh is simple — to jazz up the image of cask and present it to a younger generation that is focussed on quality, provenance and sustainability as the freshest choice on the bar. In simpler terms, it’s Steve Buscimi saying ‘how do you do, fellow kids’, only he’s standing at the bar ordering a round of Bitter.

At the end of the session I couldn’t help but ask a question: Instead of trying to modernise cask and turn it into something it very much isn’t, wouldn’t it be better to lean, hard, into its tradition? Something we’ll cover in the third and final part of this series is how, overseas, cask beer is often lionised, and seen by many as the pinnacle of how certain kinds of beer should be served. And yet in the UK we’ve labelled it as this old hat, stuffy thing, when actually it’s perhaps our greatest, gastronomic gift to the world. It’s intensely British, really, to make something so good, and then spend decades poking fun at it. It’s why I fear, despite the intention being spot on, campaigns like Drink Cask Fresh are forever doomed to fail.

Before I lived in the North, I spent a decade and a half in London, where cask is still very much loved, but the quality is an absolute crapshoot. I championed cask in London, but this was very much based on knowing where to go — the reality is that of 3000-odd pubs in the capital, I would only confidently recommend about 10 for a really good pint of cask beer. If you are trying to get people to enjoy cask beer, then the focus should be solely on the quality. I know I’m repeating myself but this is important; it should be cellared correctly, served through clean lines, and into clean glassware (I can’t stress how vital that last part is, the visual joy of a lace-lined pint glass is truly a wonderful thing to behold.)

The fact is, for the majority of people, the experience isn’t good enough. One bad pint of cask beer is enough to put someone off for life. But, flip that on its head, and then you’re only one exceptional pint of cask away from converting someone to its charms, forever. No amount of bright orange neoprene hand pull wraps are going to create that experience. But, perhaps treating it with care and a little bit of wide-eyed reverence will mean that enthusiasm is passed on to the next generation of drinkers.

When it comes to the data, however, I think we have to be careful when looking at the numbers, because although there are around 2000 breweries operating in the UK, most of which produce cask ale, in reality they are difficult to compare to one another. About 14% of total beer production in the UK is packaged in cask, the vast majority of which is produced by a handful of producers, including Molson Coors, Carlsberg Marstons, and Asahi, among others. The best selling cask beer in the UK by some distance is Sharp’s Doom Bar, a Molson Coors product.

Now, on its day, there’s nothing wrong with a pint of Doom Bar, I’ll admit. But you can’t really compare a product like this to what’s being produced up and down the country by far, far smaller producers. Small batch, artisanal and fresh-as-hell cask beer is the kind of product that people should be getting excited about. And you know what? The data says that’s exactly what could be happening.

The latest edition of SIBAs annual craft beer report, which pulls together numbers from its approximately 700 member breweries, states that the production of cask beer has increased 7%, from 46% to 53% of total member production over the past year. While this is a small shift, and one that is no doubt influenced by the collapse of the category during lockdown, I would say there is enough evidence here to feel very positive about the future for cask ale. It clearly states that the majority of beer being produced by small, independent breweries is destined for cask, and that can only really mean one thing: that more people are drinking it.

Cask beer is one of the most special products you’ll find on the bar anywhere in the world, but as an icon of cultural importance, it’s home is in the UK. While it has spread and become somewhat commoditised, there are pockets where those of us who drink it will not accept a poor pint, and as such the quality is consistently high, from pub to pub.

It’s anecdotal, and based solely on my own perception, but what if instead of trying to dress cask beer up as something it really isn’t, we go deep on its heritage and provenance, and ensure it’s served at its best, each and every time a pint is pulled. Once you’ve had a great pint, or two or three, there’s no data in the world that’ll convince you there’s a better way to serve beer.

—Matthew Curtis